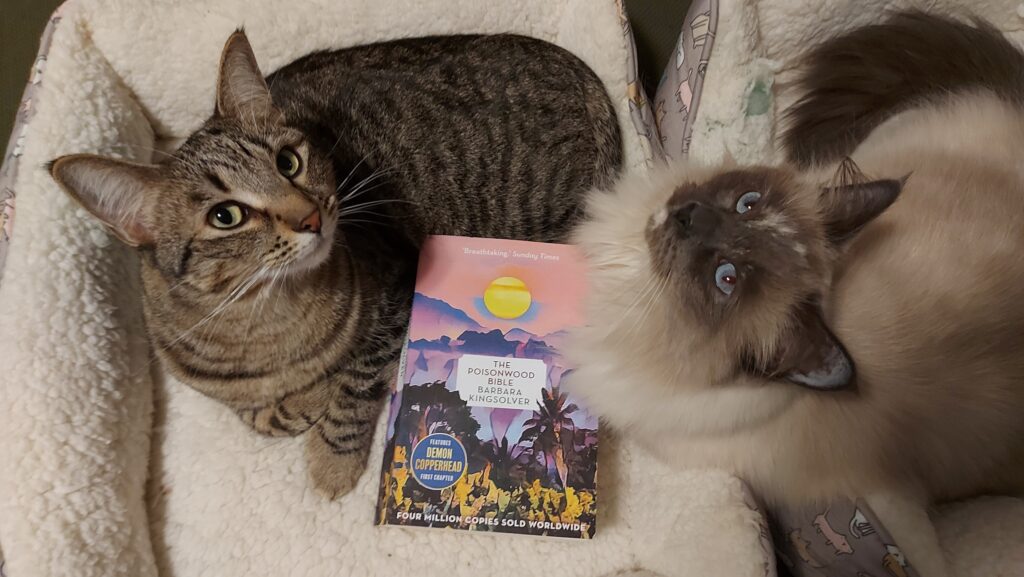

The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver

I probably never would have read Barbara Kingsolver’s The Poisonwood Bible if I had not read Demon Copperhead first, and I am so glad I did not miss out on this incredible story of family, religion and race. I completely understand now why The Poisonwood Bible is such a well-regarded novel, and I highly recommend it, just do not let its thickness deter you.

The Poisonwood Bible is about an American Baptist minister named Nathan Price who, in 1959, takes his wife and four daughters to the Congo to spread the Christian gospel and baptize African children. Nathan Price is one of those fiery Baptist preachers who has a very black and white view of God’s grace and cannot stand to be contradicted or presented with beliefs that differ from his own. He also does not give a shit about his own family and is abusive towards his wife and children.

In 1960 the Congo achieved independence from Belgium and elected its first Prime Minister, Patrice Lumumba. What followed afterwards was civil war, culminating in the assassination of Lumumba in 1965 during the coup d’etat of Mobutu Sese Seko (who had the help of America and Belgium). Mobutu was a dictator in the country he renamed Zaire until he was overthrown in 1997. When the Belgians pull out of Congo in 1960, Nathan is advised to leave the Congo because it would be too dangerous to stay, but of course he doesn’t leave, and he doesn’t let his family leave either. The Price family then suffers through drought and starvation alongside their Congolese neighbours, until one of the Price girls pays the ultimate price for her father’s hubris.

The story of Nathan Price’s mission in the Congo is told through the perspectives of Nathan’s wife, Orleanna, and his four daughters, the eldest being Rachel, who is sixteen when they arrive in the Congo, twins Leah and Adah, and the youngest, five-year-old Ruth May. Orleanna narrates her version of the story from the future after she has returned to the US and attempts to explain her complicity in her family’s downfall, and as much as I could empathize with her situation, I also could not help but feel that she failed her daughters. The daughters each take turns narrating the story as events unfold from when they first arrive in the Congo to decades later when Orleanna is an elderly woman. Rachel is quite funny with her teenage histrionics, but she most emulates American racism. Leah idolizes their father and wants to follow in his footsteps, but I think she ends up hating him the most as she learns to love Africa. Adah suffers from hemiplegia and is mute throughout most of the novel, but she is intelligent and appreciates African languages the most. Ruth May, with her youthful innocence, has the easiest time fitting in with the people of the small Congolese village that they live in. Each daughter is uniquely rendered, and I think it is a testament to Kingsolver’s characterization that my feelings for each of them changed as they each grew older and settled into her own version of adulthood based on her father’s influence and her own experience with Africa.

It is important to understand that The Poisonwood Bible is written by a white writer and is a story about white characters, so as much as Kingsolver describes the historical events of the Congo with sensitivity and treats the African characters with understanding, there are limitations to research over personal experience and the narration is coloured by the prejudices of the characters. But you can tell that Kingsolver has a great love for Africa by the way the Congo comes to life through her words. I could almost feel the heat of the African sun on my skin and feel the African dirt under my feet as I read this novel.