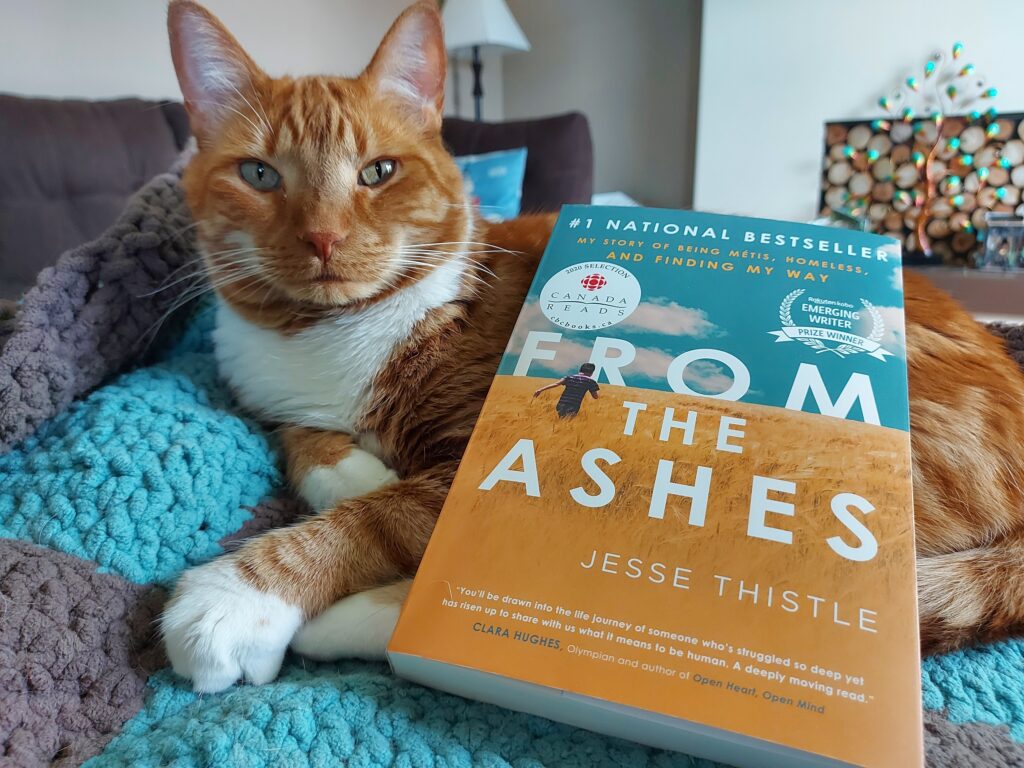

From the Ashes: My Story of Being Métis, Homeless, and Finding My Way by Jesse Thistle

I highly recommend Jesse Thistle’s memoir, From the Ashes, but I warn you that it can be difficult to read as he spent decades living as a homeless drug addict. A couple of times I had to put this book aside because it was too much to stomach. However, Jesse’s story is incredibly inspiring as he would not have written this memoir if he did not eventually have the willpower to give up drugs and get his life back on track and go to university. He now works as an Assistant Professor in Métis Studies at York University.

Jesse is Métis-Cree from his mother’s family and his father’s family is Scottish, although his paternal grandmother is also part Algonquin. Jesse was born in Saskatchewan, and his mother’s family was a big part of his life until he was about three years old, when his father essentially took him and his two older brothers away from their mother and moved them to Brampton, Ontario, which is where his father’s family lived. Jesse’s mother never made the effort to get her sons back. His father was a drug addict and a criminal; he was the kind of parent who thought it was funny to give his kids alcohol and who would leave his kids to fend for themselves for days at a time. Jesse and his brothers learned at a young age how to steal food from the corner grocery store.

One day Jesse’s father never came home, and the police showed up to take Jesse and his brothers to Children’s Aid. His father has not been seen since and Jesse does not know if his father is dead or alive. There is a “missing person” notice at the back of the book regarding his disappearance.

Eventually Jesse and his brothers were taken in by their paternal grandparents. Their grandparents did the best they could for them, but they were not very patient or affectionate people. His grandpa especially believed in the concept of “tough love” as that was how he was raised. Jesse spent most of his adult life believing that his grandpa hated him because Jesse was a drug addict and a criminal like his father, and of course realized until it was almost too late that his grandpa actually loved him.

Jesse grew up disconnected from his Indigenous roots and had to endure the racism of his peers, who called him and his brothers “dirty Indians”. Because of this, Jesse was ashamed to be Indigenous and compensated for it by brawling and getting into alcohol and drugs. He had a difficult time learning in school and could hardly read and write by the time he dropped out of high school, which makes it even more impressive that he went to university later in life and was awarded prestigious scholarships.

As mentioned above, Jesse spent decades living as a homeless drug addict. At one point he ended up on Hastings Street in Vancouver, but mostly lived on the streets in the Brampton area. He was in and out of jail as a petty criminal. Honestly, I do not know how he managed to survive, even after reading his memoir. It is just so heartbreaking to read about his experience as homeless and a drug addict, and to know that there are people just a block from my work who are experiencing the same thing. I wonder how Jesse’s family were able to refuse to have anything to do with him during that time and not help him get off drugs, but at the same time I can understand how they gave up on him because he kept blowing every chance he had to get help. His memoir highlights the failure of rehab, which takes drug addicts in long enough for them to be weaned off the drugs, then just spits them back out again onto the streets where they just end up doing drugs again.

In 2006, Jesse ended up in jail again after a robbery attempt and convinced a judge to let him go back into a drug rehabilitation program. He finally got clean, finished his GED, met the woman he would eventually marry, and reconciled with his family, including his mother and her family. He reconnected with his Indigenous roots and that led to his university studies involving his people, the Métis. Jesse’s life is an example of the importance of Indigenous people being able to connect with their communities and their culture, not being taken away from them, like the lost generations who were forced into residential schools by the Canadian government.