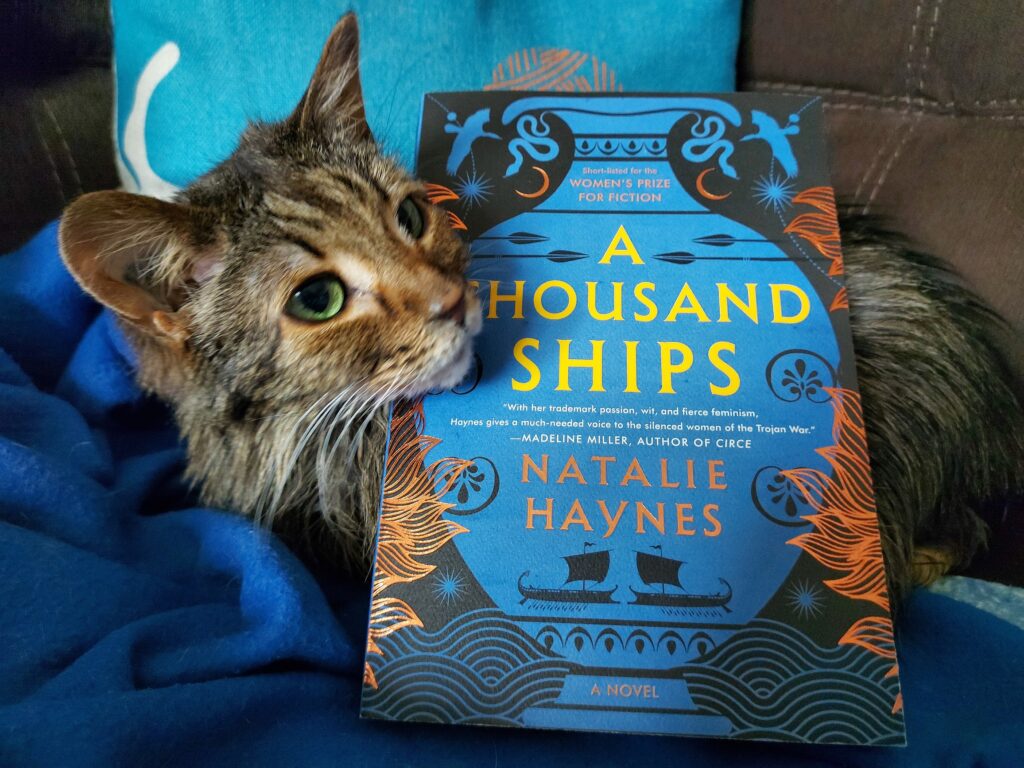

A Thousand Ships by Natalie Haynes

Lately, I seem to be reading a lot of novels by women that are a revival of Greek mythology, novels based on classical Greek literature written mainly by men. There is Madeline Miller’s The Song of Achilles (the first review I published on my blog) and Circe, and now A Thousand Ships by Natalie Haynes. I really enjoyed reading A Thousand Ships. It’s a feminist retelling of the Trojan war which focuses on the women who are usually side-lined in epic tales about the male heroes of Greek and Troy, and it’s purpose is to show that women can be heroes too even if they don’t fight in wars (with the exception of the Amazons).

The women in A Thousand Ships illustrate that there is a quiet kind of heroism in being left behind when their husbands, brothers and sons go to war. The women of Troy, who watch their husbands, brothers and sons be slaughtered by the Greeks and then watch their city be pulled down, survive rape and capture by the Greeks and keep their heads held high as they face their post-war fate to either become slaves or be sacrificed to appease the Gods (F— men, always sacrificing young women. Slit your own damn throats to appease the Gods).

There are four main narrative threads in A Thousand Ships. The first involves the muse Calliope, who is called upon by an unnamed bard to write an epic poem for him. She wants to tell the stories of the women of the Trojan War and show that they were just as heroic as the men. The bard doesn’t really like this idea, but Calliope doesn’t care what he thinks. She’s determined to tell their stories.

The second narrative thread is the women of the Troy. As already mentioned, they have survived the sack of Troy to be divided up among the Greeks to become their (mainly sex) slaves. These women are mourning the men, their male children and the city that they loss, but at the same time they are aware that the war was pointless and could have easily been avoided if Helen had just been given back to her husband in the first place. But men don’t really listen to their women very well, especially when what they say makes sense. Helen is a universally despised character and my only criticism of this novel is that we do not get to have her story told from her own perspective.

The third narrative thread involves Penelope’s letters to her husband, Odysseus. This is probably my favourite narrative in the novel as each letter gets progressively snarky. There have been a lot of stories told about Odysseus’ cleverness and his wild adventures after the Trojan war, but the truth is that Odysseus abandoned his wife and child for twenty years. The Trojan war was ten years, but it took him another ten years to finally make his way home to his family and he spent those ten years pissing off Gods and cheating on his wife. Meanwhile Penelope waits for him to come home, fending off boorish suitors who think Odysseus is dead, and getting more and more upset as the years go by and as she hears his adventures told to her by bards.

The final main narrative thread involves the Greek Goddesses, whom I would not praise as being heroic at all because of how capricious and manipulative they are, especially when it comes to humans. It is through this narrative thread that we learn how the Trojan war really started (and you can’t blame Helen for everything).

All these narrative threads about the Trojan war told from female perspectives make for an entertaining read which I’m sure you will find goes by too quickly. I highly recommend you take the time to read this novel.